Intro to Kaktovik Numerals

Note: The text for Kaktovik numerals has only been tested for the most recent edition of Google Chrome (Version 130.0). Please check your browser and setting if you are unable to view all of the content in this page.

The Kaktovik numerals were developed only about 30 years ago in the village of Kaktovik. This system was developed by middle schoolers and their teacher once they realized the difficult in describing numbers in Iñupiaq.

The reason for this diffuculty is because, as previously described, the vocabulary for numbers in Iñupiaq follows a base 20 system. The accepted word for forty is Malġukipiaq, the accepted word for 800 is Malġuagliaq, and so on. Instead of every place value being a factor of 10, every place value is a factor of 20.

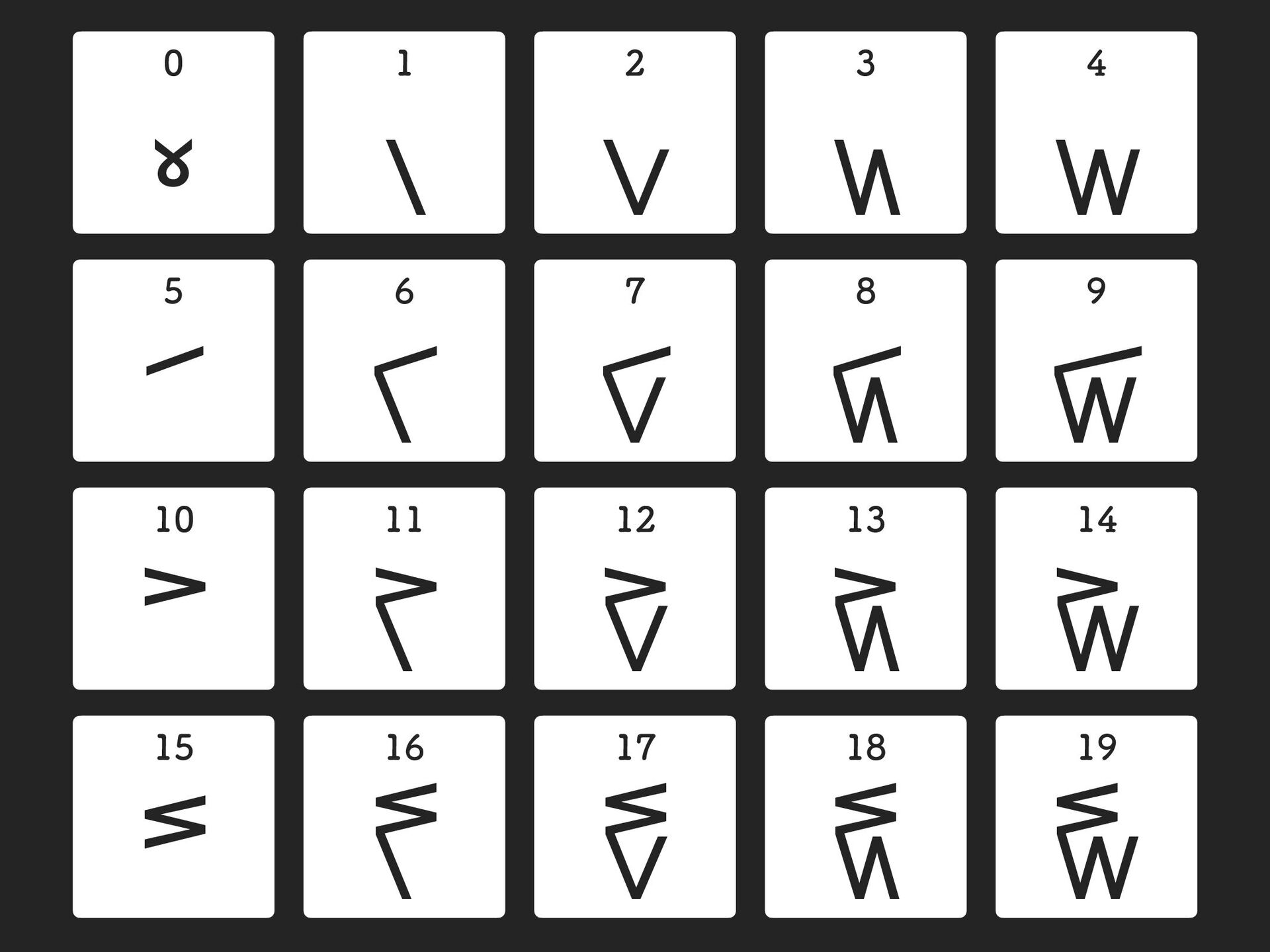

The Kaktovik numeral system uses a series of strokes: up to four vertical strokes to represent numbers 1 through 4, as well as up to three horizontal strokes to represent numbers 5, 10 and 15. This allows for a combination of 19 different numbers. The system also has a symbol to represent 0.

The number 20 is written as , or 10. 21 is written as , 22 is written as and so on. 30 starts to become a disconnect, since it is written as , or 1(10). This continues on through , or 1(19), before increasing the leading number to reach . We see that 40 as written as 20.

This disconnect will only continue to increase in the higher numbers. For example, , or iḷagiññaq, is equal to 400. Adding another zero to the end to make , or atausiqpak, creates a number that is equal 8000. This trend will continue, increasing each factor of 10 by an additional factor of 2.

Converting From Decimal Numbers to Kaktovik Numerals

The money model described in the vocabulary sections of this site can be very helpful for converting numbers below 400. Remember that we separate in terms of 100 dollar bills, 20 dollar bills, 5 dollar bills and 1 dollar bills (ignoring 50 dollar bills and 10 dollar bills for this). Think about what bills you need to make each of the decimal numbers, and use a number of strokes in the Kaktovik numeral syste.

For example, take the number 17. You would need 3 five dollar bills, which would be written as akimiaq, or . You would also need 2 one-dollar bills, which would be written as malġuk, or . Putting the two together, we get .

To convert 96 to Kaktovik numerals, we start with the number of 20 dollar bills you would need, 4, to make (with a zero at the end to help us know that they are twenties). We also need 3 fives () and 1 one (). Putting all of it together, we get .

Looking at a larger example, 278 would need 2 one hundred-dollar bills (), 3 twenty dollar bills (), 3 five dollar bills () and 3 one dollar bills (). Putting all if together, we get .

Going into numbers that are bigger than 399 requires us to think outside of this convenient system. Now we need to imagine larger denominations of money: the 400 dollar bill, represented with and the 2000 (five 400s) dollar bill, represented with . For example, 5600 would require 2 two thousand dollar bills () and 4 four hundred dollar bills () to get . To get numbers bigger than 7999, we have to keep multiplying our denominations by 20.

If the idea of 400 dollar bills and 2000 dollar bills isn't helping you, a more mathematical method of converting from decimal numbers to Kaktovik numerals is to divide in a sequence of powers of 20. First, determine the highest power of 20 that the number can be divided by. Divide the decimal number by that number, then take the remainder and divide by the next power of 20, all the way until you reach the single digit at 19 or lower.

For example, the biggest power of 20 that 10612 can be divided by is 3 (203 = 8000). 10612 can only go into 8000 once, with leaves us with our Kaktovik numeral as and a remainder of 2612. We'll divide the by 400 (202) to get 6, giving us a Kaktovik numeral of and a remainder of 212. We divide this by 20 to get 10, which we write as . Finally, we simply convert this last remainder of 12 to a Kaktovik numeral, . Once we add all of these up, we will get our full Kaktovik numeral:

(8000)

(2400)

(200)

+ (12)

(10612)

Just because these numbers look different and have a different number base doesn't mean that they follow different rules of math. The main difficulty in doing math using these numbers just comes from use having a very built in perception that 10 mean ten, when it could just as easily mean 2, or 16, or 20. Once you get past that, there are ways that you could use the way the numbers look to make it easier to make calculations.